I spent the last week studying and discussing gospel culture, which is, most simply, the unity between Christians that flows from union with Christ. The majority of my classmates were pastors, so we spent a lot of time talking about how to foster gospel culture through preaching and shepherding. Naturally, I was concerned with how musical worship can subtly but effectively make or break the gospel culture of a church.

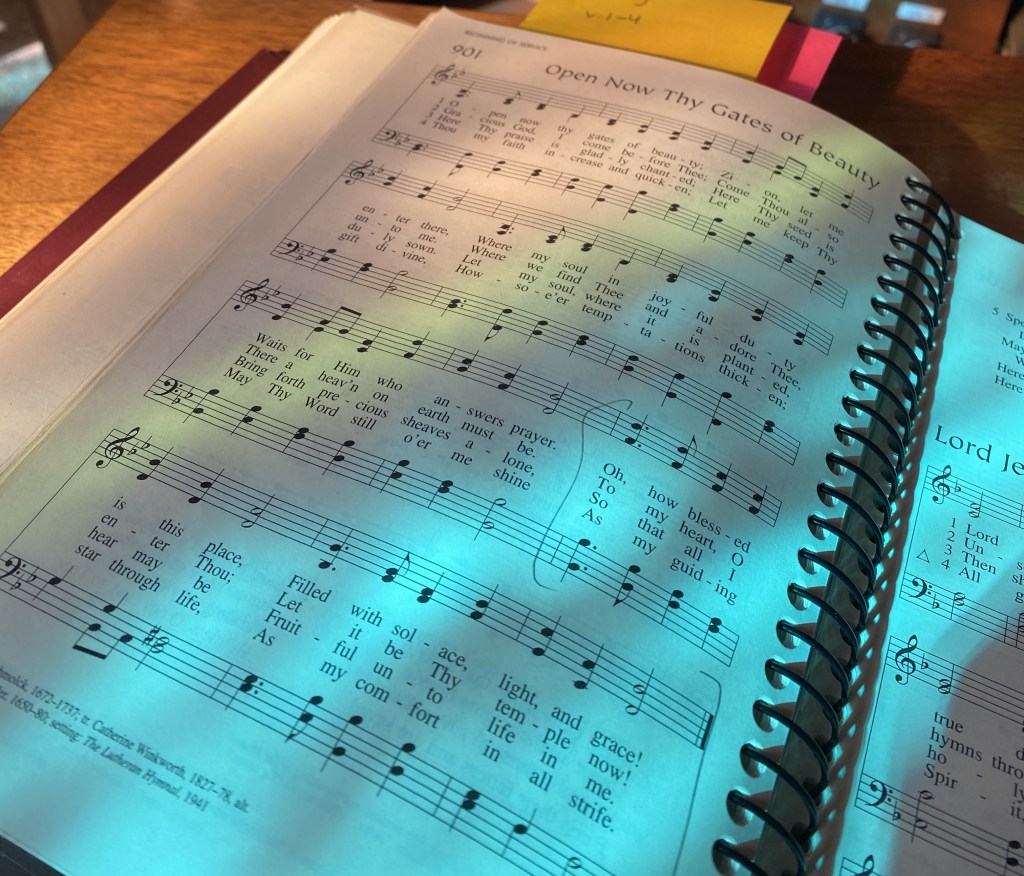

Scripture commands us to sing not only to God (vertical worship) but to one another (horizontal worship). Ephesians 5 tells us to “address” one another in song and Colossians 3 implies that we should “teach and admonish” one another, both in speech and in song. Addressing, teaching, and admonishing can be accomplished in any musical style; however, as I led worship yesterday morning, I was struck by how the enduring hymns of our faith are crafted to help us accomplish these ends. They are composed to praise God, certainly, but also to honor, encourage, convict, and unite Christians.

In short, the hymns are composed to cultivate gospel culture—vertically and horizontally. Whether or not you are a hymn-lover, I invite you to consider the following points.

When we sing hymns, we…

1. Teach one another.

Singing is mnemonic, so I am thankful that each hymn I play includes scripture citations to ensure that, when I memorize my favorite verses, I memorize truth. I consider well-written hymns “sung commentaries” that communicate, clarify, and celebrate the Word of God. When we sing the best hymns together, we internalize and revel in the Word as musical study partners.

While I don’t believe singing is only a tool for teaching and memorization, I do believe this is its most important function. Why? Because without a solid grasp of gospel doctrine, we can’t have gospel culture. That’s just a fact. Without knowing and believing the good news of forgiveness and new life in Christ, what hope do we have of living together as forgiven, changed people?

2. Identify with one another.

Each Sunday, I lead a traditional service and participate in a contemporary service. Aside from musical style, a major difference between the two is the use of plural vs. singular pronouns. Traditional worship often employs “we/us/ours” or “you/your/yours” language, while contemporary tends toward “I/me/my” pronouns. Our faith is personal and communal, so we should expect to see a balance between individual and group language.

Yesterday, only one of four songs in the contemporary service included plural pronouns, and even these could easily have been singular. It was a beautiful worship set, but the imbalance is worth noting. The traditional service, by contrast, included five hymns. Of these, three were overtly communal, with “we” or “you” language throughout.

The hymns often remind singers that they are not merely soloists but members of an ensemble—a heaven-bound choir of saints united in Christ. When we use communal language, we more readily identify with one another’s burdens and joys because, really, they are ours as well. We should never abandon individual expressions of praise, but gospel culture requires us to look not just up but out—not just to Christ in us but to Christ in those around us.

3. Confess with one another.

I don’t know of any contemporary songs of confession other than “Lord, I Need You” by Matt Maher, and this song doesn’t confess anything other than our general dependence on God. I genuinely like this song and think it’s worth using in worship. However, for gospel culture to thrive, we need to confess our sins to each other and glory anew in the grace of Christ. My hymnals have entire sections dedicated to confession, and while I certainly don’t use these songs exclusively, I try to program one or two regularly so singers have the chance to practice confession.

“But why do we need to practice confession together?” you might ask. “Surely worship is a time of praise! We can get through the more distasteful stuff (confession, repentance, forgiveness) on our own, right?”

Sort of…Look, your church is your family, and how your church worships will bleed into how you live. What isn’t practiced corporately is unlikely to be practiced privately. When we sing songs of confession, we are working it into the rhythms of our lives. We are flexing our repentance muscle so that it comes more readily when confessing alone to God or a trusted friend.

4. Encourage one another.

A few weeks ago I played “Fight the Good Fight” as my closing hymn and used a baseball organ riff as my introduction. I did this for fun, as well as to emphasize a theological point: Christ has won the race, but we still have to run, perhaps singing “Charge!” as we press onward.

The hymns are fundamentally concerned with glorifying God but often accomplish this by encouraging His people. So many hymns joyfully address Christ-followers, cheering them on and sending them forth with determined hopefulness. How could this not also glorify the very “God of endurance and encouragement”? (Romans 15:5).

5. Honor one another.

I recently played a delightful hymn that calls different people to praise God with surprising specificity. Contemporary worship tends toward generalities, but the hymns are unafraid of precision. Again, the primary goal of this hymn is glorifying God, but it does so by identifying the glory evident in His people and their vocations (2 Corinthians 3:18).

The overarching message of this hymn goes something like this: “Children praying simply, praise God! Builders laying solid foundations, praise God! Scientists studying creation, praise God! Athletes exercising your bodies, praise God!”

While always directing singers to God’s work and worthiness, this hymn also honors what is good, true, and right in His image bearers (Ephesians 5:9). We are called to dwell on whatever is true, honorable, just, pure, lovely, commendable, excellent, and praiseworthy, so why do we shy away from honoring the workmanship of God in other Christians? (Philippians 4:8).

6. Remember one another.

I will always love G.K. Chesterton’s description of tradition as the “democracy of the dead.” By this he means that, through traditions, the dead continue to have influence; they continue to have a voice, a “vote” in how we live and worship.

Christians who pass away are absent in body but present with the Lord; they’re worshiping Him now, and when we worship, we join in the activity to which all creation—past, present, and future—is called. When we sing old hymns, we remember and respect the work of those who came before. Through the songs they wrote, cherished, and preserved, we worship with them across time and look forward to worshiping with them in eternity. How amazing is that?

7. Include one another.

This final point relies on singers’ ability to read music, but it’s worth mentioning nonetheless. Hymns are written for ensembles; they assume vocal diversity and are written out so all ranges can participate in a suitable, attainable, non-distracting manner. I know several altos in my church choir who are extremely thankful that our hymnals include low harmonies!

Contemporary worship, with its simpler composition, welcomes newcomers into the songs of the Church. This is worth acknowledging and praising. However, finding keys that include the most voices and do not only suit leaders or soloists seems to be a more natural strength of hymns. Granted, in either style, the inclusion of diverse ranges and abilities depends more on the sensitivity of the songwriter and worship leader than anything else. Still, it’s worth learning from the ensemble composition of the hymns, which may be more vocally inclusive than the soloist-congregation style of newer songs.

Conclusion

If you do not regularly sing hymns, I hope this post encourages you to start doing so more often. If you do, I hope this post reinvigorates your love for these treasures of the faith and revives your dedication to not only sing about the gospel but to press into the beautiful community it begets.

Leave a comment